I’m going to stray into the autobiographical today and, as you may have noticed, the first person. I loathe the first person, because it’s implicit in this form, but the subject demands it.

My grandfather died today, but I’m not talking about that, yet.

My father is a minister. Every Sunday he stands in front of a couple hundred people and does his best to provide some kind of magnetism for the compass of their lives. Take away the magic, the fable, the systematic oppression of thousands of years of mythology and indoctrination, and at its core you’ll find people sitting together and sharing a communal event; a collective suspension of disbelief to navigate the troubled waters of everyday life.

As long as I’ve known him, which is to say my whole life, to one extent or another, my dad has been accosted by young potential seminarians. They ask him about pursuing the clergy as a vocation, and his response is always the same.

–Can you do anything else?

Their response is predictable; some variation of:

–Huh?

His riposte:

-Because if you can do anything else, anything at all, do it.

He keeps it in his back pocket. It’s a wonderful little joke to him and, like all good jokes, is achingly true.

I wish more ministers of theatre gave such advice, but they generally suckle at the academic teat and fear for their own solvency. If they honestly told any of their young charges, “This isn’t for you. Can you do anything else?”, they would be preaching to empty pews. Their funding would be cut. Their dreams of tenure would dwindle. Honesty is just too costly in theatre, because the instructors care more for themselves than their vocation, or the future of their craft.

I’m told I’m too aggressive and antagonistic, but tonight I just don’t care.

My grandfather died today. He was 94 and had a tumor in his lung. He refused treatment. He was ready, and I’m proud of him for that. I’ll get to him in a moment. Don’t worry. He has time.

Sometimes I think I do this, this thing, this gross and sublime display, this Theatre, this theater, this whatever this is, because I’m just in too deep. I earned an MFA at the expense of unspeakable debt, but am cautiously proud of a registered and notarized mastery of this art, yet I don’t consider myself an artist. It feels too much like a choice. I’ve neglected too many relationships, half-assed too many jobs, and abandoned too much comfort to go back now. Credit, I tell myself, is for suckers. An AmEx is a signifier of complicity. It may as well be a red armband around a khaki sleeve.

This thing I do, to which I’ve sacrificed all or most of what is considered valuable by people who value such things, is far, far bigger than myself. That moment when the audience breathes with you, when several hundred people take a collective breath and to one degree or another experience a shade of some shared human something is worth more than I could have earned as a doctor, or a lawyer, or a theoretical physicist (all of which are fantastic things, and more people should do those things for the right reasons outside of the meritocracy and its tired, predictable demands). It’s an instant, but it’s worth the whole universe. Is there a single thing in life better than weakening the walls between people? Success is defined by how many human beings recognize themselves in each other, right?

Could I do anything else?

Absolutely not.

Several years ago, I was doing what was probably my fourth A Christmas Carol. Among other things, I was The Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come. I’m 6’3”, and this was probably my most important qualification for the part, because the costume was basically a giant backpack with a puppet that extended two and a half feet or so over my head, with two wide skeletal arms I operated from within a giant black cloak. In costume I was over 8 feet, and my job was to basically follow a robotic light around the stage and make some meticulously choreographed gestures. I could see, more or less, through a fine mesh that was hopefully, usually, in front of my eyes.

One night, well into the run (which consisted of 10 show weeks by and large—this is not to complain, but to give context), when much of the show, particularly the stuff you do inside a giant black puppet that reeks of your own sweat, is pure muscle memory, when your brain can just check out (again, inside a giant puppet), I had a remarkable experience.

Scrooge was realizing the depths of his sins as he watched the Cratchits mourn their poor Tiny Tim. I was bored. I wanted to scratch my nose, but couldn’t justify swinging my giant, bony fingers towards my nose, which was the midsection of my enormous glow-in-the-dark puppet. I took a deep breath, and tried to focus on the audience. There, in the second row, was a middle-aged man, weeping. He wasn’t crying. He wasn’t having a thoughtful trickle of tears slide down his cheeks. He was sobbing; heaving. Beside him, attached to him, was a boy of about 8 with a smooth, freshly shaved head, watching quietly, at peace.

There was a comfort there that you cannot find in any place in the world. They had no idea I was staring at them as father mourned in expectation and son found peace–I still lose my breath at the thought of it–I have no idea where he found that peace, but his eyes were clear and bright and full of understanding.

Theatre is a religion, where we find mutual peace and understanding in our communion. That moment between father and son (and me, parenthetically), constantly challenges and informs my understanding of theater, or Theatre, or whatever this is, this gross and sublime display.

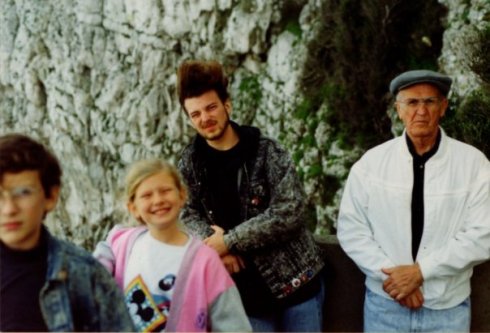

My grandfather died today. He was 94. He fought during the entirety of the second world war. He had two children. He buried two wives. He was kind and decent and grew wonderful, juicy tomatoes. He had a slice of white bread with every meal and drove an ancient Chevy truck until he couldn’t anymore, a moment he recognized before anyone else because he was an examiner at the DMV.

I may not be able to attend his funeral, because last minute tickets to Louisville are unreasonably expensive, and because when someone asked me

–Can you do anything else?

I said no.